The fact that, in the year 2025, a significant amount of money is spent to remind people to buckle their seat belts is wild to me. First unveiled by Volvo in the late 19th century, the seat belt is an astoundingly efficient and life-saving safety invention.

Yet after generations of formed habits, seat belt usage still hovers around 90%, leading to thousands of annual fatalities. Fortunately, there are still people who seem persuadable enough about the topic that an occasional public safety announcement might move the needle.

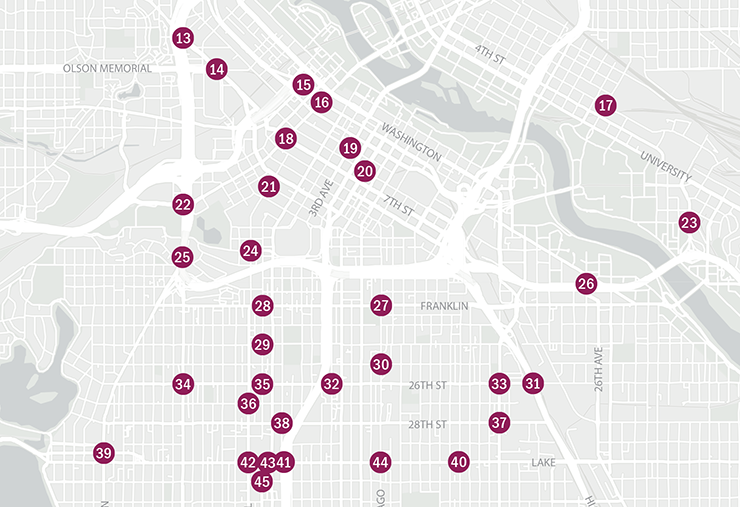

This is to say safety seems like a problem that’s more cultural than logical. This is also to say that the unfolding traffic safety camera pilot program in Minneapolis might take a little while to reap rewards. The city just unveiled a map of locations, and the first cameras will be installed this summer.

The timing is right

On the one hand, the speed cameras come at the perfect time for Minneapolis. Post-COVID safety data is moving shockingly in the wrong direction, and speeding and fatalities are up here and across the country. Minneapolis crashes disproportionately affect working-class neighborhoods and vulnerable users like bicyclists and pedestrians, making this an acute equity issue. Meanwhile, as Axios reported Tuesday, traffic enforcement by the Police Department is down over 80% since the pandemic.

Something has to be done, and short of spending billions to reconstruct every city street, cameras are the only solution on the table. It’s in the interest of the vast majority of residents to make sure they work well and get rolled out smoothly.

Minneapolis released its map of proposed sites for its new camera pilot two weeks ago. The pilot was authorized by the Legislature in 2023for five years, and if they work well they could be used indefinitely. Later this summer, the city will narrow down the 51 possibilities to five initial camera locations, slowly growing the number of deployed cameras to 10 or more locations by 2026.

“The goal initially is to make sure all of our systems are working great and that we have the staff capacity to manage the work of processing warnings and citations,” Ethan Fawley, the city’s Vision Zero Program Coordinator, told me. “Then we will expand as we’re able.”

Looking at the map, there are a few wrinkles. For the most part, the sites reflect the city’s extensive crash statistics — which have been published for years under the Vision Zero program — but the geography is not quite one-to-one.

For example, the state law requires that cameras be within a half-mile of a school. (This is generally a great idea, as only the most sociopathic drivers remain blind to the logic of slowing near schools.) Fortunately for Fawley, there are schools throughout Minneapolis. While the rules do take a few places off the table, most of the city is still in play.

The second limit is more difficult. For its initial locations, in order to avoid inter-jurisdictional negotiation, the city has chosen to avoid streets that are “owned” by higher levels of government. That poses a minor problem, as county and state roads are consistently the city’s most dangerous spots. The aim here seems to be to quickly iterate, and to keep things running as smoothly as possible. For now, Minneapolis is putting cameras near (but not on) key roads such as Cedar Avenue and Lake Street. In the future, it should be easier to get government partners on board with the program.

The resulting map might seem weighted in certain areas of the city — for example, the Whittier neighborhood has a large concentration of potential camera locations — but the actual cameras will be more evenly distributed. Some neighborhoods just happen to have a lot of city-owned streets with poor track records, often located near highway ramps.

That makes them prime candidates for safety tools, but precisely where the cameras are located will be based on ongoing public engagement. That’s something the city has already begun and will continue throughout the summer.

Proving cameras can work

The short-term goal for Minneapolis planners isn’t to solve speeding right away, but rather to prove the (formerly contentious) concept that speed cameras can work well. That’s something that’s more complicated than most people realize. Planners are trying to avoid any political minefields that might emerge from having cameras deployed and enforced in any manner that seems arbitrary or unfair. This is why there’s a one-month warning period, as well as a warning for first-time offenders.

Likewise, the city has to hire new staff to administer the cameras, a process that’s more nuanced thanks to an initial warning period and the tricky details around establishing a driver’s identity. No doubt there will be a learning curve for both staff and the public as the process unfolds. The three initial “traffic control agents” will be housed under Minneapolis Regulatory Services Department, which also oversees things like building and restaurant inspections.

“Based on the experience in other cities, when the system initially launches will be when violations are at the highest level,” Ethan Fawley told me. “They’re going to be people that are still learning about the system, and so we want to make sure we can handle that flow.”

The very idea of speed cameras are a red flag to a certain subset of drivers, people who have long viewed driving above the speed limit as an entitlement. But that’s precisely the cultural problem that the city’s ongoing Vision Zero initiative is aiming to fix. The loose regulation of U.S. automobiles and drivers leads to everyday risky behavior that would be unheard of in most peer countries.

That’s why safety cameras will not be a panacea, single-handedly eradicating traffic fatalities. They’ll have to be part of a larger cultural shift, efforts that reshape our expectations around how we drive in urban areas. As the ongoing seat belt example shows, that process will take a lot of time, which is why the speed camera pilot is moving particularly slowly. When it comes to a new technology, it’s important to make a good first impression.

Bill Lindeke

Bill Lindeke is a lecturer in Urban Studies at the University of Minnesota’s Department of Geography, Environment and Society. He is the author of multiple books on Twin Cities culture and history, most recently St. Paul: an Urban Biography. Follow Bill on Twitter: @BillLindeke.