The legislation, passed last year, requires the city to establish a new 311 option for tenants to report and request inspection of empty units creating hazards in their buildings. It was supposed to go live in early August.

William Alatriste/NYC Council Media Unit

Councilmember Carlina Rivera, co-sponsor of Intro. 195, with advocates at a rally for the bill in June 2023.

At the end of the 2023, the City Council passed Intro. 195, requiring the city to establish a new 311 option for tenants to report and request inspection of vacant units creating hazardous conditions in their buildings.

The new law, its sponsors say, aims to ensure landlords are keeping empty apartments in good condition. It would also help policymakers get a better sense of how widespread vacancies actually are across the five boroughs, including stabilized units being “warehoused”—or deliberately kept off the market by property owners holding out for higher rents.

“There are many numbers out there at different estimates, but the fact of the matter is that there are empty units,” said Councilmember Carlina Rivera, who represents the east side of Manhattan and sponsored the bill, along with Upper West Side Councilmember Gale Brewer.

The lawmakers said they and their fellow representatives often hear from constituents about empty units in their buildings, and problems stemming from them.

“They’ll complain there’s garbage, it’s having sanitation issues, there’s vermin, there’s mice, there’s roaches, sometimes even toxic fumes,” Rivera added. “And so we know that those unoccupied units are not only potential homes for someone who is experiencing homelessness or who needs a place to stay, but it’s also creating quality of life issues for neighbors.”

The bill, now known as Local Law 1, was supposed to take effect in early August. But the city’s Department of Housing, Preservation and Development (HPD) told City Limits it’s still “actively working to implement the requirements,” to the chagrin of its sponsors.

“To ensure effective compliance, we must follow established processes to secure budget allocations, contract for necessary technology upgrades, and adjust our systems for new workflows, including handling new types of complaints, violations, and program changes,” HPD Spokesperson Natasha Kersey said in a statement. “In the meantime, we continue to use all of our existing tools to keep tenants safe from issues like heat and hot water outages, pest issues, leaks, lead-based paint, and other housing quality concerns.”

The late implementation comes amid other legislative standoffs between the City Council and Mayor Eric Adams’ administration (which is currently embroiled in a federal bribery investigation). City Hall has refused to move on another package of bills passed by the Council last year that would expand eligibility for the city’s rental voucher program, called CityFHEPS; that dispute is currently playing out in court.

Brewer and Rivera said HPD has known for months about the impending requirements of the bill, including a fiscal impact statement that estimated the costs of rolling it out at $150,000 a year, which they provided ahead of the most recent budget negotiations.

“I’m sorry, but when the City Council passes a law and it becomes law, then it is the law, and you need to find funding to enforce the law. If you need to ask the Office of Management and Budget for more money, you should do that,” Councilmember Brewer said an in interview with City Limits.

Gerardo Romo / NYC Council Media Unit

Councilmembers Erik Bottcher, Gale Brewer and Carlina Rivera at a rally Thursday pushing HPD to implement the bill.

HPD had opposed the bill when it was under consideration, telling lawmakers at the time that vacant and off-the-market units represent just a small portion of the city’s overall housing stock, and that there are already agency processes in place for reporting and inspecting empty apartments for violations.

“In our experience, units that are vacant are generally not a hazard to neighboring tenants, and in many cases, are vacant because an owner is in the process of renovating or correcting conditions prior to putting the unit back on the market,” Lucy Joffe, assistant commissioner for housing policy at HPD, said at a Council hearing in June 2023.

Creating a separate reporting process focused specifically on vacant units would “divert critical resources away from HPD’s enforcement while not creating any measurable increase in the supply of safe and affordable housing,” she said.

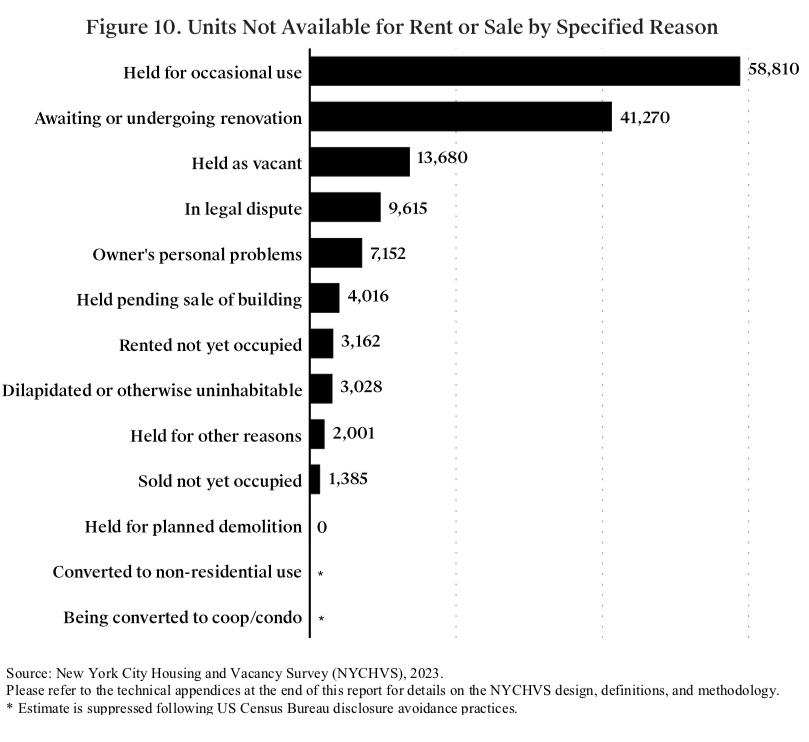

In 2023, the city’s City Housing and Vacancy Survey counted 230,200 units that were “vacant but not available” to rent for one or more reason, down from 353,400 in 2021. More than 58,000 of those were apartments held off the market for “seasonal, recreational, or occasional use”—sometimes known as a pied-à-terres, or second homes.

Of the vacant and unavailable units that year, 26,310 were rent stabilized; more than 41,000 were “awaiting or undergoing renovation.”

“In a housing shortage, whatever it is—one point, some minuscule number or percent of available housing units in the five boroughs—you need every unit you can get,” Brewer said. “So the fact that there is warehousing is very frustrating.”

Property owners, for their part, have largely argued that landlords aren’t keeping units off the market for nefarious reasons, but because aging stabilized units often need significant repairs, which they say they can’t afford to make while collecting regulated rents.

“The cost of this work is very high, often over $100,000 per apartment,” Adam Roberts, a policy director with the group previously known as the Community Housing Improvement Program, now the New York Apartment Association, testified to the Council at its June hearing on the bill. “Without loans, owners do not have the financial means to pay for this work. As a result, these apartments have been left vacant en masse.”

Brewer and Rivera, however, both pointed to resources and recent policy changes to help assist with repairs. The last state budget deal raised what’s known as the Individual Apartment Improvement (IAI) cap, which limits how much landlords can increase rents on stabilized units to compensate for renovations. And the city launched a $10 million program last year to help rehab and rent out empty apartments (though owners said that funding falls far short of actual need).

“We should certainly expand the programs that help landlords that might be financially stressed,” Rivera said. “But the fact of the matter is, there are a lot of units in these buildings that are owned by larger, financially equipped corporations that could bring these units back up and and into code.”

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.